|

|

|

|

«O Russian Land, you are already

behind the hill! ! The night was long in falling. Slowly the

light of the sunset faded and dark mist covered the plain. The

nightingales fell quiet and the call of the ravens was heard.

The men of Rus barred the great plains...»

|

|

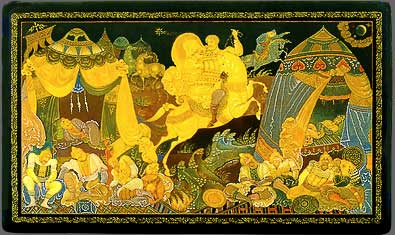

"The Lay of the Host of Igor" |

N.Lukina. "The Lay of the Host of Igor"

Box. 1997 Palekh |

"The Lay of the

Host of Igor, or Slovo o polku Igoreve, is the enigmatic

masterpiece of medieval Russian literature. Written on the occasion

of Prince Igor's unfortunate campaign against the Polovetsians in

1185, "The Lay of the Host of Igor" is unanimously

acclaimed as the highest achievement in Russian literature of

the Kievan era.

Sometime between 1788 and 1792 Count

A. I. Musin-Pushkin, a bibliophile and amateur of Russian antiquities,

acquired a number of old documents from Archimandrite loil of

the Monastery of the Saviour in Yaroslavl'. Among them was an

unfitted manuscript concerning the campaign of Prince Igor against

the Polovetsians in the spring of 1085. Although it was thought

that this group of documents dated from the sixteenth century,

Musin-Pushkin later wrote that he believed the manuscript of

the Prince Igor tale was written in a script characteristic

of the late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries. Several

copies of this manuscript were made, including one for Empress

Catherine the Great.

The first printed edition of the poem,

including the old Russian text and a translation into modern

Russian, appeared in 1800. The work of Musin-Pushkin, the historian

Karamzin, and two other scholars, this first printed edition

contained a number of errors.

When Musin-Pushkin's Moscow house burned

during the Napoleonic invasion of 1812: his priceless manuscript

collection, including the original manuscript of Prince Igor,

was destroyed. The "Catherine Copy" of the poem was

preserved, although unfortunately it too contains a number of

obvious errors. Working on the basis of the "Catherine

Copy" and the first edition of 1800, scholars have reconstructed

the original text. Nevertheless, there remain several defective

and disputed passages in the poem.

Who was the author of "The Lay

of the Host of Igor", and when was it written? One can

only presume that he belonged to Igor's court, was a warrior,

and, as is evident from his Lay;, was very familiar with

the life and environment of the steppe. Even less can be said

of the literary antecedents of the work and of the epic tradition

previous to it. It is true that the writer of the Lay

often mentions Boyan, a bard who apparently lived in the eleventh

century, but no details are known either of his life or of his

poetic works.

|

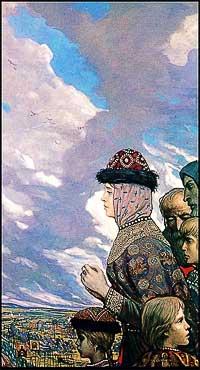

L.Fomichev "Prince Igor in the camp of the Polovetsians"

Box. 1972 Mstera |

Prince Igor is himself

a well-known historical personality. A prince of Novgorod-Seversk,

he was the grandson of the famous Oleg of Chernigov and the

cousin of Grand Prince Svyatoslav of Kiev. Igor was an active

participant in the internecine wars of his time. He began his

campaign in 1185 to drive out these nomadic invaders, who, every

year, would raid Russian territories, burn the cities, and take

the inhabitants as slaves. Living in movable camps, the Polovetsians

were cattle raisers and warriors. The enmity between them and

the Russian farmer, artisan, and trader was similar to the classic

enmity between the Chinese and the nomadic peoples living beyond

the Great Wall. But in the case of Russia there was no Great

Wall and there was no strong emperor standing at the head of

a highly developed, centralized state apparatus. In Russia there

were only open plains and warring princes. A curious entry in

the Ipat'yevskaya Chronicle for the year 1159 indicates that

as early as that date the lands along the middle Dnieper were

already becoming deserted as a result, at least in part, of

the ravages of the Polovetsians

In 1185 Grand Prince Svyatoslav inflicted

a serious defeat on the Polovetsians, taking prisoner Khan Kobyak.

The Ol'govichi (Oleg's descendants), did not participate in

this victory. But Igor and his brother Vsevolod, Prince of Trubchevsk

and Kursk, hearing of the Polovetsians' defeat, undertook a

campaign of their own against the Polovetsians, toward the Donets

River. This undertaking was a failure.

There was apparently opposition to this

campaign among members of Igor's retinue. On May 1, 1185, there

was an eclipse of the sun, which the Nikonovskaya Chronicle

describes: "A Portent. That same year, in the month of

May, on the fist day, there was a portent in the sun; it was

very dark, and this was for more than an hour, so that the stars

could be seen, and to men's eyes it was green, and the sun became

as the [crescent] moon, and from its horns flaming fire was

emitted; and it was a portent terrible to see and full of horror."

Although the Russians interpreted this phenomenon as an evil

omen, Igor insisted that the campaign continue, saying, "No

one knows the mysteries of God. God is the maker of this sign

and of the whole world. And whether that which God does to us

is for good or for ill, this too we shall see."

In the first battle, on Friday, May 10, 1185, the Russians were

victorious over what was apparently merely a rather small scouting

detachment of Polovetsians. Igor now urged retreat, saying,

according to the Chronicle: "Lo, God with His strength

has inflicted a defeat on our enemies and [has given] us honor

and glory. Lo, we saw the Polovetsian armies that were many.

But were they all gathered here? Let us ride the night . . ."

Igor may well have sensed the impending disaster. But his nephew

Svyatoslav (who was only nineteen) objected, noting that his

men were tired and that if the main body of Russians were to

retreat, some of his men would be left behind on the road. Igor's

brother, "Wild Ox" Vsevolod, the most dashingly heroic

personage in Prince Igor, sided with Svyatoslav, and the Russians

pitched camp for the night.

|

L.Fomichev. "Igor's escape"

Box. 1997 Mstera |

|

Prince Igor's estimate of the situation

had been correct. The following morning, Saturday, Polovetsian

troops "began to appear like a forest." The Russians,

alarmed, held a council of war. Some argued for retreat, but

now Igor insisted that they stand their ground, saying: "If

we flee we shall ourselves escape, but we will leave the black

people [the common foot soldiers]. That will be a sin against

us from God, having betrayed them. Let us go: we shall either

die or be alive in one place." So the princes and voivodes

(officers) dismounted and went into battle against the Polovetsians.

All day they fought and into the night.

When Sunday morning dawned the battle was still raging. And

then the Turkic mercenaries, the Koui, panicked and began to

fall back. Igor, who had been wounded in the arm and was on

his horse, set out at a gallop to rally them. Thinking that

they, having caught sight of him, were indeed returning to the

battle, Igor galloped back toward his own men. Unfortunately,

the Koui did not return to the fight but continued their retreat;

only one man, according to the Chronicle a certain Mikhalko

Georgiyevich, turned back. When Igor was within an arrow's flight

of his own men he was taken prisoner. At this moment - one of

the most dramatic in the story - Vsevolod was seen by Igor,

surrounded by the enemy and fighting fiercely. Believing all

was lost; Igor "asked for his soul's death that he might

not see his brother fall."

But neither prince was killed. The Polovetsians

carried the day and decisively defeated the Russians, taking

many prisoners, including Igor, Vsevolod, and Igor's son Vladimir.Following

their defeat of the Russians, the Polovetsians decided to counter

the Russian attack with an invasion. They entered Rus' with

two armies: the one commanded by Khan Gza, the other, under

Khan Konchak. Although both armies caused much destruction and

laid waste many Russian districts, the result, typical of all

the Polovetsian raids, was not conclusive.

According to the Chronicle Prince Igor,

early in his captivity, became deeply troubled by feelings of

guilt. Igor felt that it would be dishonorable for him to try

to escape: "For the sake of glory I did not flee then [during

the battle] from my retinue, and now I shall not flee ingloriously."

But at least two of Igor's counselors, the son of a chiliarch

(commander of a thousand men) and the prince's groom, advised

otherwise, feeling that the Polovetsians, returning unsuccessful

from their campaign, might in frustration kill the prisoners,

especially the princes and voivodes for whom sufficient ransom

had not been forthcoming. The eighteenth-century Russian historian

Tatishchev wrote that because the chiliarch's son was the lover

of Khan Toglyy's wife, he heard from her of plans to kill the

Russians and there upon alerted Igor's groom. According to the

Ipat'yevskaya Chronicle, both the chiliarch's son and the groom

warned Igor of the danger.

Fortunately for Igor, a Polovetsian

named Ovlur (Lavur) offered to help Igor escape. One evening

when Igor's guards were drinking koumiss (fermented mare's milk),

the prince stole from his tent to meet Lavor, who had two horses

ready on "the other side of the Tor River," and made

his escape. Khans Gza and Konchak pursued Igor but failed to

recapture either him or Lavor. Crossing the Donets River, the

two men arrived at the town of Donets. Igor then went to Kiev,

where he was greeted with great joy by the two grand princes,

Svyatoslav and Ryurik.

|

Robert C. Howes |

© 2004 Artrusse

Email

|

|

Russian history

|

The Lay of the Host of Igor

Invasion

Alexander Nevsky

The battle of Kulikovo

The Time of Troubles

Peter the Great

The Desembrists

|

under construction

under construction

under construction

under construction

under construction

|

|

«Would it not be fitting, brothers.

To begin with ancient words

The sorrowful song of the campaign of Igor,

Igor Svyatoslavich.

Now let us begin this song

In the manner of a tale of today,

And not according to the notions of Boyan.

Now the wizard Boyan,

If he wanted to make a song to someone,

His thought would range through the trees;

It would range like a grey wolf across the land,

Like a blue eagle against the clouds.

His words would recall the

Early years of princely wars:

Then he would release ten falcons

Onto a flock of swans;

The first swan to be touched,

It would be the first to sing:

To old Yaroslav, to brave Mstislav,

Who cut down Rededya before the

Armies of the Kasogians,

To the handsome Roman Svyatoslavich.

Now Boyan, brothers, would not

Release ten falcons

Onto a flock of swans,

But his magic fingers would

He place on the living strings,

And they themselves would

Sound forth praises to the princes...»

|

|

|

«From early morning of the fifth

day,

They trampled under foot the army of pagan Polovetsians.

And, sowing the field of battle with their arrows,

They carried off the beautiful Polovetsian maidens,

And with them, gold, and silken cloth,

And thick red and violet velvet, with ornaments.

And with horse cloths, and capes, and cloaks,

They began to lay roads

Across the swamps, across the muddy places.

This they did with all

The precious brocades of the Polovetsians.

The crimson banner,

The white pennon,

The crimson horse-tail ensign,

And the silver lance:

All - to brave Svyatoslavich.

Oleg's brave nest slumbers

In the field; far has it flown!

Yet it was not born to suffer wrong

From hawk, or from falcon,

Or from you, black raven, Pagan Polovetsian!

And Gzak flees like a grey wolf;

Konchak, following him, heads for the Great Don.

The second day, very early,

The blood-red sky heralds the dawn.

And black clouds move in

From the sea to cover the Four Suns.

And in these clouds the Blue lightning glitters.

There will be great thunder

And rain will fall like arrows from the Great Don.

And spears will be blunted here,

And sabres will be dulled here,

Against the helmets of the Polovetsians,

On the river Kayala,"

Near the Great Don...»

«..The voice of Yaroslavna is

heard on the Danube:

An unseen cuckoo, she sings at dawn:

"I shall fly," she says,

"As a. cuckoo, along the Danube.

I shall wash my sleeves of beaver

In the river Kayala.

I shall cleanse the bleeding wounds

On the mighty body of my prince."

Yaroslavna weeps at dawn

On the walls of Putivl', saying:

"O Wind, O Sailing Wind! Why,

O Lord, do you blow so strongly!

Why do you drive the arrows of Khinova

On your peaceful wings

Against the troops of my Beloved!

Is it not enough for you,

Flying on high beneath the clouds,

To rock the ships upon the Blue Sea!

Why then, O Lord, did you scatter

My happiness about the feather-grass!"

Yaroslavna weeps at dawn

On the walls of Putivl' city, saying:

"O Dnepr, Son of Renown!

You cut through the mountains of stone.

Through the Polovetsian Land!

You cradled the long boats of Svyatoslav

Till they reached the army of Kobyak.

Then cradle, O Lord my beloved to me,

That I may not soon send my tears to him, to the Sea.

.Yaroslavna weeps at dawn

On the walls of Putivl' city, saying:

"O Bright and Thrice-Bright Sun!

For all you are warm and beautiful!

Then why, O Lord, did you send

Your hot rays onto the troops

Of my Beloved!

On the waterless plain,

Why did you warp their bows with thirst

And close their quivers with sorrow...»

«The sea tosses at midnight,

The whirlwind comes in clouds

And God shows Prince Igor the way

From the Polovetsian Land,

To the Russian Land,

To the Golden throne of his fathers.

The dusk of evening is gone:

Igor sleeps, Igor wakes,

Igor, in his thoughts, measures the plain

From the Great Don to the Little Donets.

And Ovlur whistled beyond the river

for a horse, Warning the prince:

"Prince Igor should not delay!"

Ovlur shouted, the earth shook,

The grass quivered, and the Polovetsian tents

began to move.

And Prince Igor sped as an ermine to the rushes,

Like a white duck to the water.

He leapt on the swift horse

And leapt from it, like a grey wolf.

And he fled toward the bend of the Donets;

He flew like a falcon through the mists,

Killing geese and swans morning, noon and night,

If Igor flew like a falcon,

Then Ovlur ran like a wolf,

Shaking from himself the cold dew.

And both harrowed their swift horses.

And the Donets said:

"O Prince Igor! Great is your praise,

And great is the chagrin of Konchak

And the joy of the Russian Land!"

And Igor said: "O Donets!

Great is your praise,

Who cradled a prince on your waves,

Spreading out green grass for him

On your silver shores;

Clothing him with warm mists

In the shadow of a green tree.

You watched over him

As golden-eyes on your waters.

As sea gulls on your waves,

As black ducks on your winds."

"Not like this," he said,

"Was the river Stugna with its shallow flow,

Devouring foreign streams and currents.

And widening toward its mouth.

It bore away Prince Rostislav

And imprisoned him in the depths,

Near the dark shore.

Rostislav's mother wept

For the youth, Prince Rostislav.

The flowers were despondent in pity,

And the trees, in sadness, bent to the ground."

It is not magpies that chatter!

It is Gzak and Konchak who pursue Igor!

Now the crows do not caw,

The jackdaws are silent,

And the magpies do not chatter.

Only the snakes slither.

The woodpeckers, with their tapping,

Show the way to the river,

And the nightingales tell of the dawn with happy songs.

Gzak speaks to Konchak:

"If the falcon flies to his nest,

Let us shoot the little falcon With our gilded arrows."

Konchak says to Gzak:

"If the falcon flies to his nest,

Let us entangle the little falcon

With a beautiful maiden.»

|

Translated by Robert C.Howes

|

|